It feels like I’ve only been asleep for minutes when I feel a toe discreetly, if not quite gently, poking me in the ribs. It’s Shakur, looming over me with a piece of plywood and a hammer. “Get up,” he says, as he would to any of his sisters. “We have work to do and you are in my way.”

I blearily rub my eyes as I sit up and look across at Asra and Enas. Asra looks like she could use another couple of hours of sleep herself. Enas, however, springs up from her mat and begins her normal breakfast-making and child-wrangling with a spring in her step. Sleep deprivation is no match for the excitement of an actual wedding.

The good news about last night is that I feel really sure that Enas is, in fact, excited about this wedding and this marriage. Twice during our mostly-silent watch under the grape vines Enas borrowed my cell phone and called Yusuf, speaking quickly and quietly and with urgency but not hostility. Whatever was causing the brouhaha, it was apparent that Enas and Yusuf weren’t invested in it. They want to get married. This is both reassuring and sad: that a family disagreement of some sort could keep them from getting married is distressing. But that they communicated calmly and were supportive of each other throughout the maelstrom seems like a great sign.

By the time the house phone rang at 2 a.m., Enas had been dry-eyed for a while. She even managed to sound calm and almost disinterested when she answered, responded “yes” a few times, and then gently hung up. Then she turned to us and grinned as she said “It’s all okay. Let’s go to bed!” I wanted answers so badly I literally itched — or maybe that was the mosquitoes, grateful that our outdoor vigil had left me even easier to munch. But I was also exhausted, and I barely even woke when Shakur and his parents clattered loudly back into the house two hours later.

Now I move myself out of the way as Asra and her younger sisters quickly move all the furniture out of the living room. This is no small feat, but the boys don’t offer to help, as they’re busy hammering together a plywood platform and positioning it at the end of the room farthest from the windows. As Shakur drives in the final nails, Bakar straightens up and says to me “Come help me move the chairs back here.”

I look around, surprised that he spoke first to me and not to one of his sisters, as he normally would. I realize no sisters are close to hand. In fact, it appears that the house is empty except for the three of us. I’m shocked.

“Where did everybody go?”

He rolls his eyes. “They went to have their hair done, obviously.”

“But they left me here!” I feel stupid, but this is really unusual.

Bakar looks like he’d like to roll his eyes again. “Your hair is already straight,” he says, and marches off towards the chairs we need to move.

*=*=*=*

By the time the ladies all return, with their beautiful curls straightened painfully into combed-out bobs, the boys have transformed the living room. The plywood platform has been covered with a small, pretty rug. Two of the formal armchairs have been placed on the platform like thrones, and Um Shakur’s precious potted plants have been arranged around them artfully. Lastly Shakur tacked a string of plain Christmas lights up in an arch behind the whole arrangement. It’s simple and inexpensive but it looks lovely. It contrasts starkly with the rest of the house, which has been stripped of everything movable, from furniture to doilies.

The two back rooms are stuffed to the gills with everything that usually goes in the rest of the house, so it’s complicated for all of us to wedge ourselves into the master bedroom, but that is obviously what we need to do when Um Shakur discovers that I haven’t changed yet. Every female over the age of six (and a few under six!) crams around the bed while I awkwardly strip and put on my new thobe. Years ago I bought an antique wedding thobe in Jerusalem and it never occurred to me to bring it to Jordan with me, so I had to run out to Irbid and buy this one after Alice and I received our wedding summons. It is made of synthetic fabric and the approximation of a traditional embroidery pattern on my chest and down my legs is made of cheap metallic thread that itches against my bare skin. But it is greeted with universal acclaim. Um Shakur even says, with not-so-mild surprise, “That’s perfect. You picked a great dress!”

The problem arises when I pull out my jewelry from my dusty backpack. I’ve brought my nicest things: a white-gold and diamond choker and tiny diamond post earrings in silver studs. Um Shakur literally snorts. “Yeah, no,” she says. “Asra, go get my gold, this isn’t going to work.” Despite my protests, she fastens two gold bracelets onto each of my wrists and then adds a heavy gold locket around my neck. Absolutely none of it is anything I would have chosen to wear, but it doesn’t matter. I’m a daughter in the family lineup today and I’m not going to look cheap. In a pitiful attempt at self-defense I say “My necklace is white gold, you know. It is gold. And it’s a real diamond!” Um Shakur gives me the stink-eye.

We hear voices in the main room and then the door pops open to reveal Alice’s branch of the family in their very finest clothes and with equally straight hair across the board. Nobody is wearing an ishaar to hide the expensive blowouts, either. All of “my” younger sisters and Alice’s are wearing matching knee-length satin dresses in a lovely deep purple that I know Um Shakur has painstakingly sewn for them over the last weeks. Only the oldest sisters in each family have bought clothes for the occasion, and Asra turns to complement her cousin Samara on her lovely new dress. We all notice at the same time the peculiar, shocked expression on Samara’s face. And that she’s looking at me. And then bursting into laughter.

“It’s… the same… dress!” she manages to choke out.

Before we can even ask for clarification, Samara’s mother — Um Shakur’s sister Um Ali — edges her daughter aside and climbs carefully over the end tables into the bedroom. And we all see what she means. Um Ali is wearing the same dress I am, although fortunately her traditional embroidery has been approximated in copper colors where mine is blue. Alice and I saw her dress for sale when we were shopping for mine, and Alice had briefly considered buying it herself, but we had decided it would seem too matchy-matchy. Thank goodness!

“Good grief,” I say. “I know this is a small country, but you’d think that if I buy a dress at one end of it and you buy a dress at the other, we wouldn’t end up with the same dress.”

Um Ali seems totally unperturbed by the situation. “Well, obviously we both picked the best dress,” she says. Then she starts in on her sister with a list of suggestions for improving the front room situation before the guests arrive.

*=*=*=*

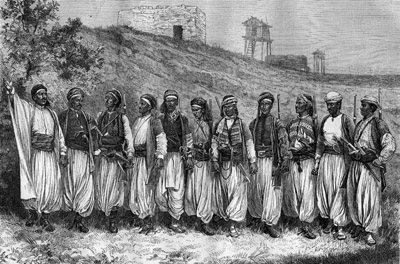

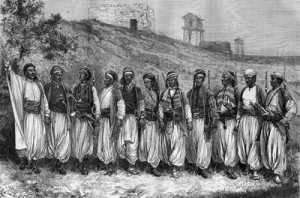

The house was packed for an hour and a half before we even had a bride to celebrate. Outside, Shakur and his father greeted arriving men and offered them tea and seats in one of the dozens of plastic chairs set out in rows. But most of the plastic chairs are empty as every man capable of standing is doing the dabke, a traditional line dance. Well, every man who isn’t our immediate family. Shakur and Bakar look exhausted as they ferry huge trays of cake slices and bottles of Coke products around to all the guests. The women inside are dancing blissfully free of ishaar and jelbaab, but therefore no men are allowed inside the house except the bride’s immediate kin. Even then, Shakur and Bakar keep their eyes carefully trained on the floor as they come in and out to refill their trays in the kitchen, lest they make anybody uncomfortable.

Inside it is complete chaos. Every relative and friendly neighbor available for inviting is here. Music blares through the sound system flanking the empty throne-chairs and women ululate and dance. Um Shakur circulates and shakes hands with every woman there, and it takes me a few minutes to realize that many of the handshakes actually include a transfer of money, after which Um Shakur tucks whatever she’s received into the puffy sleeve of the blouse she’s wearing under her traditional Bedu jumper-dress. Sometimes the guests will nod in my direction and ask who I am. I’ve overheard her repeatedly saying “What do you mean? That’s my daughter!” with a wicked, quiet glee, and then moving on without providing further clarification. She isn’t smiling any more than usual, but I suspect Um Shakur is having a blast.

Finally Enas arrives in a dark sedan. Removing her from the dark sedan is a team effort, as her hoop-skirts would do Scarlett O’Hara proud. The silvery gown is sleeveless and has a sweetheart neckline that actually shows cleavage. Enas’s hair is piled precariously up on her head and she’s wearing a startling amount of makeup, most of which appears to feature glitter. She also looks terrified as her brothers and father usher her into the house, more or less hiding her naked shoulders from the male crowd as they go. In short, she looks exactly like she should, and she sits in what looks like an unpleasant combination of embarrassment and horror in her throne as the older women of the village chant traditional praise-songs in her honor.

It is another thirty minutes before the most important event. In the distance we hear gunfire. Alice is standing next to me and says “You know, there was a time in my life when that wouldn’t have seemed normal,” and I know exactly what she means. In this context, gunfire means Yusuf and his family are arriving. They probably started a similar party of their own this morning, and once all the guests had arrived they loaded them up onto a couple of little buses and drove all the way from Mafraq here. Yusuf and his immediate family are in a dark sedan themselves, but the windows are rolled down and every window features a young man leaning out and shooting into the sky. I know they’re shooting real bullets, too — a couple of times a year, a bullet goes astray or comes down to earth too fast and kills someone. But the shooting is too big a part of the culture to be abandoned, so Alice and I just step away from the window.

Yusuf’s female relatives and friends somehow manage to squeeze themselves into the house, turning what had been a huge party into an Austen-era “crush.” It is almost impossible to move, so I position myself as discreetly as I can against one wall and try not make eye contact with anybody who might be inclined to say “Hey, let’s watch the American dance!” I keep my eye on Enas, wondering if she’s likely to need a container into which she can vomit. She looks like she might.

Suddenly, Enas looks up, her eyes lighting up for the first time today. The drum-sounds from outside have come closer, and the solid mass of women jostles urgently to the left and the right like the parting of the Red Sea. Yusuf strides into the room like some twenty-something demigod, flanked by a variety of men I don’t know, all singing and drumming as loudly as they can. The guns, thank goodness, appear to have been left outside. Yusuf is escorted right up to the empty throne. Now Yusuf and Enas can sit next to each other on the thrones as the singing, dancing crowd reaches fever pitch. It must be impossible to hear each other very well, but occasionally they lean toward each other and exchange quick comments. Enas is always stoic, but together they look easy and comfortable, for all that Yusuf is clearly feeling cocky and Enas is clearly feeling awkward. My heart is glad for them.

*=*=*=*

The party is over at some sudden signal that I completely miss. Yusuf’s posse boards the buses and heads back to Mafraq, drumming and shooting with unflagging enthusiasm. The house reminds me of my college’s ballroom after an all-campus party, except that the sticky spilled drinks on the floor don’t smell like old beer.We extricate Enas from her complicated dress and she changes, with an air of profound relief, into sweatpants and a t-shirt. The family shifts into overdrive, the boys tearing down the platform as the girls pour sudsy water all over the floors and start vigorous scrubbing. Once the mess has been squeegeed into the drain in the kitchen, we replace the furniture, and within about an hour the house looks more or less as it usually does.

After they have chased the smaller persons into bed, Um Shakur and Enas join the rest of the semi-adults in the living room. It’s a little curious for us to all hang out in here, because this space is usually just for formal visitors. It feels like we’re still riding the wave of celebration. As if to reinforce the fact, Asra joins us carrying a small cake decorated with “Mabruk Yusuf & Enas!” and we each enjoy a piece. Um Shakur contorts herself up into her own sleeve and extracts a mound of crumpled bills, which she counts as we eat. When she has straightened it into a neat pile folds it up and hands it wordlessly to Enas. Enas takes it just as silently.